Chlorine harms marine life – and we don’t even need it

Chlorine is widely used in water treatment – and with good reason. It is an effective, readily available, and cheap agent for wastewater treatment. But when it comes to the marine environment, chlorine has a dark side that is often overlooked.

Even in tiny amounts, chlorine is highly toxic to fish and other aquatic life. Trout larvae die at concentrations as low as 0.006 mg/L, and at just 0.1 mg/L, most marine plankton are killed. Once released, chlorine can also react with organic matter in seawater to form trihalomethanes (THMs) – a group of persistent, carcinogenic compounds that remain in the environment long after the chlorine itself has dissipated.

A fragile food chain under threat

Chlorine’s toxic effects are not limited to fish. Shellfish, such as oysters, are affected at levels as low as 0.01 mg/L, where they struggle to pump water through their systems. Plankton, which form the foundation of marine food chains, are particularly vulnerable. When plankton populations collapse due to chlorine exposure, entire food chains – including commercially important species – are affected.

Adding to the problem, chlorine becomes even more dangerous when water contains substances like ammonia, cyanide, or phenols. The resulting chemical reactions can produce compounds that are even more toxic than chlorine itself.

Tiny amounts of chlorine can be lethal

Even extremely low concentrations of free chlorine are highly toxic to aquatic organisms:

- 0.006 mg/L: kills trout fry within two days

- 0.01 mg/L: recommended maximum for all fish and aquatic life

- 0.1 mg/L: kills most marine plankton

- 1.0 mg/L: lethal to oysters

By comparison, drinking water standards for humans allow up to 4.0 mg/L in some regions – a level fatal to marine life.

Invisible and long-lasting effects

One of the most concerning effects of chlorine use in wastewater treatment is the formation of THMs. These compounds are formed when chlorine reacts with decaying organic matter in water – a common scenario in grey or black water on ships.

Unlike chlorine, THMs don’t break down quickly. They persist in the environment, accumulate in living organisms, and some – such as chloroform – are linked to human cancer. Their impact is long-lasting, both for marine ecosystems and for people exposed through seafood or drinking water.

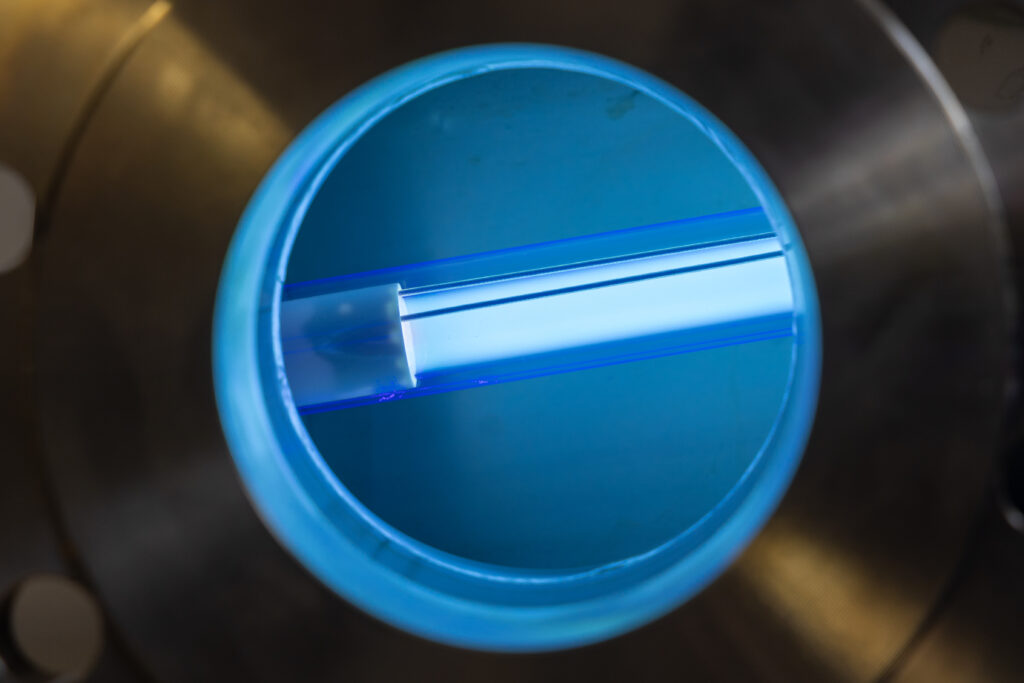

Chemical-free treatment with UV and biology

At G&O Bioreactors, we have chosen a different path. Our systems do not use chlorine or any other harmful chemicals. Instead, we combine biological treatment with UV disinfection technology from Van Remmen UV technology to achieve a 99.9% reduction in faecal contamination – fully in line with the latest IMO standards and regulations for special areas such as the Baltic Sea

- UV disinfection is highly effective and leaves no chemical residues.

- Biological treatment breaks down organic matter in a natural way, reducing operational costs over time.

- Our systems require no chemical handling, generate no THMs, and demand minimal maintenance.

“Chlorine-based disinfection methods can lead to the release of persistent toxic byproducts that accumulate in marine environments, disrupting aquatic life. UV disinfection provides an effective, chemical-free alternative that neutralises pathogens without compromising ecosystem integrity”

Bert Jan Otten, Van Remmen UV technology

Chlorine reacts – and becomes even more toxic

Chlorine becomes significantly more harmful when it interacts with other substances commonly found in wastewater, such as:

- Ammonia (from urine): forms toxic chloramines

- Cyanides and phenols: can produce extremely toxic compounds like cyanogen chloride and chlorinated phenols

- Low pH levels: increase chlorine’s toxicity due to chemical speciation

These combinations are typical in untreated or poorly treated black water.

THMs – invisible and persistent toxins

When chlorine reacts with decaying organic matter in grey or black water, it can form trihalomethanes (THMs), including:

- Chloroform – a probable human carcinogen

- Bromoform and dibromochloromethane – environmentally persistent and toxic

THMs do not break down easily. They accumulate in marine organisms and persist in ecosystems long after the chlorine has dissipated.

Cleaner ships. Safer oceans.

For shipowners and operators who want to reduce their environmental footprint without compromising performance, our approach offers a proven and forward-looking alternative. While chlorine-based or electrolytic systems may offer short-term convenience, they carry long-term ecological risks.